Back in June of 2016, I traveled to my hometown of Toledo, Ohio to meet with four Arab families of refugees from Iraq and Syria. I wanted to understand what kinds of refugees the United States admitted through its legal immigration program and what they dealt with once they got here. Now that President Donald Trump has banned legal immigration from a handful of Muslim countries, including Syria, these stories could help shape the conversation on any retooling or elimination of refugee assistance policies.

Toledo

Once known as a manufacturing center in the American “Factory Belt,” Toledo is now like many other Rust Belt towns with its shuttered factories, chronic unemployment, and population decline. Since 1970, the city’s population has declined by an astounding 27.1%. But there is one group of people in Toledo that is increasing in number – Arab refugees from Syria and Iraq.

Toledo bears an undeniable Arab footprint in local commerce, government, and civic life. Syrian-Lebanese immigrants arrived as early as the 1880s, seeking economic opportunity and freedom from strife and political oppression. Immigrants continued to arrive throughout the twentieth century, often for the same reasons. The immigrants themselves, their children, and grandchildren worked hard to become a well-respected and influential community in the city.

Over nearly a century and a half, the Middle Eastern community of Toledo has grown to include Syrians, Lebanese, Palestinians, Egyptians from a variety of Christian and Muslims sects, and is highly integrated into all aspects of Toledo’s social, cultural, business, and political life.

Presently, the city government promotes refugee resettlement through a “Welcome Toledo” initiative, partly in hopes of diversifying its human capital. Many refugees, from the Middle East, for example, come with professional backgrounds in medicine, dentistry, and entrepreneurship that can help jumpstart the city’s local demand for more college-educated workers. Toledo, for its part, provides an affordable and welcoming environment for newcomers, with its dozens of parks and recreation areas for families, small and large businesses, and social justice oriented interfaith communities.

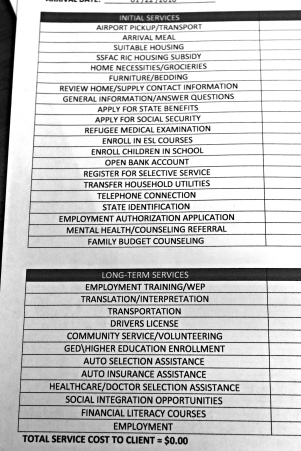

I met the families in their homes and places of work; tagged along during medical visits; and joined in community gatherings with other refugees and their new American neighbors. The photographs and vignettes in this story are the product of those interactions, which were facilitated by Shane and Lona Lokatos. The husband-wife team runs Social Services for the Arab Community (SSFAC), a Toledo-based grassroots organization that serves over 400 families at various stages of immigration, political asylum, or refuge.

Nashwaan

Nashwaan is a Christian refugee from Mosul, Iraq where he worked in construction. He currently lives in Toledo with this wife and three children ages 10, 18, and 21. He volunteers at a local church, where he practices speaking English with other churchgoers.

Members of the Islamic State in Iraq kidnapped Nashwaan in Mosul three years ago. The militants who took him eventually formed into what we know today as “The Islamic State” – or “da’esh.” He avoids sharing specific details of the incident except to say that when he was rescued, he and his family fled to Kurdistan, where then his 15 year-old daughter Wasan was kidnapped by another group of militants. Upon her release, they escaped to Jordan.

While in Jordan, Nashwaan saw refugees helping one another, despite their hardships. He involved himself in a variety of social welfare activities, including the collection of clothing and other household supplies for refugee families. After two years, the International Organization for Migration determined that Nashwaan and his family would receive asylum in the United States.

Going to the U.S. “was a chance to finish what I started in Jordan,” where refugee families helped one another.

Nashwaan wanted to do the same for those in the United States. In January of 2016, he and his family got that chance when they arrived in Toledo.

Nashwaan told me that fresh wounds from back home still exist among the refugee community. Suspicions of allegiance and questions of loyalty persist.

Sometimes people whisper about whether someone is a member of mokhabarat, the notorious domestic spy agencies in Arab countries, and other times wonder if you’re against the Iraqi and Syrian regimes.

Still, Nashwaan observed the benefits of mixing with other refugees, noting that Arabs of different backgrounds can interact more openly. Nashwaan has even developed close relationships with other refugees who are Muslim, something he thinks would not be possible if he still lived in Iraq.

Waseem, Madeleine, and Wasan

Nashwaan’s three children are in different stages of learning. He explained that his 21 year-old son Waseem last attended school in 2009. The gap is a common pattern for refugee children in transition.

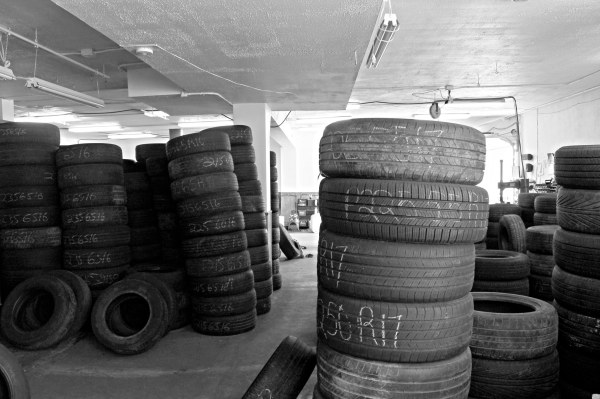

“He no longer wants to study.” Instead, he works at an auto repair shop in town and wants to be a truck driver.

18-year old Wasan looks and acts like any other American teenager glued to her smart phone. But her story is much darker than her siblings. Her kidnapping by militants in Kurdistan left marks of trauma that will take time to heal. Still, she takes English language classes and hangs out at church in her free time. Sometimes she attends a monthly women’s social gathering between refugees and longtime Toledo residents. Wasan wants to go to school, maybe become a doctor or a teacher, but she has no plans to attend classes in the near future.

Nashwaan’s daughter Madeleine, age 10, attends Whiteford Elementary School and already speaks English fluently. Nashwaan has high hopes for her. She has made friends and integrated into school life quickly.

Nashwaan recognizes the transition is harder for the older children, but he is steadfast in his view that “the most important thing is that they finish their education.”

Zein

Four years ago, Zein, a 29 year-old Christian refugee from Damascus, Syria sat in the waiting area with his pregnant wife at the U.S. Embassy in Jordan. They watched family after family depart in tears as consular officers rejected visa applications. Miraculously, the Embassy approved their application.

As soon as they arrived in the United States, they applied for political asylum and reached out to the one person they knew in the country, an acquaintance that lived in Toledo, Ohio.

“I was lucky to get a visa to come to the US. We didn’t expect it – we went to the U.S. Embassy to try. We were desperate.”

“It was a great experience coming to Toledo. I believe if we went somewhere else, we couldn’t do what we have been able to do here. We met really good people here that helped us a lot. They gave us a chance to focus on a few things and they helped with things we couldn’t do ourselves – to help us move on.”

“I had my own business in Syria. We had a dry cleaning business; I had my own shop and got new machines. I was 16 when I started my own shop. I was hiring folks and managing.”

“I started my auto repair business in Toledo on the first of July. It was a lot of luck and work. I probably can’t do this in Europe since I don’t speak French like my brothers. I didn’t speak English before I got here either but English is pretty easy to learn. Plus I don’t think there is the same opportunity in Europe that there is in America.”

“It wasn’t hard to decide to leave Syria. Since 2011, the fighting started started in Daraa, and then Homs was very bad, and then what happened in Damascus was very bad. It was crazy. They destroyed it completely. I didn’t think it was a good idea to go to Jordan and just sit there. I couldn’t do anything there.”

“Between Toledo and Syria, there is a big difference. I’m not going to say its better – its just different with friends and community. In Syria, we see each other every single day. Here, we have to make a date to see a friend. Life is much busier here and much more expensive. But in Syria you don’t make as much money as you do here – but it is much cheaper. I won’t be able to get a new car, a big house, and my own business in Syria.”

“Last time I was in Syria was four years ago. I would love to go back to Tartus for just five days. We have all our memories back there. But one of the best points I do really like about here are the schools. I am very happy with those schools and the kids will have a better chance than we had.”

Jihaad and Fahad

Jihaad and Fahad live in Toledo with their 18 year-old son. In Aleppo, Syria, Jihad worked as a dentist and Fahad worked as a physician. Currently, Fahad cleans an office building and Jihad searches for dental assistant positions.

“My name is Jihaad Sankary, I am an American Citizen. I was born in California. My family and I lived in Aleppo, Syria and I have worked in my dental clinic as a dentist. As a result of the tragic circumstances that Syria is currently going through and what my family and I went through (I do not want to mention the details because it is very difficult) we decided to flee to Turkey because it is the closest refuge to Aleppo. I had nothing in mind but to get safely to Turkey without being harmed. In March of 2013 my family and I fled to Gaziantab [sic], Turkey. As we arrived in Turkey, I decided as an American citizen to take refuge in the American Embassy located at Ankara. The Americans gave immigration status to my husband, my son, and myself, but my daughters were over 21 and not granted immigration status.”

“We applied for refugee status at the UN for our daughters and it’s been two years since then. When we inquired about our status, we found out our file was totally closed at the UN. There was some confusion and they thought our daughters already went to America.”

“During this time, my daughters also kept on going to the UN office to find out why their files were closed. Our congressional representative here in Toledo began working on the issue, and after several attempts from her, the files were re-opened.”

A variety of bureaucratic misunderstandings and inexplicable delays in the Turkish government and United Nations system further delayed efforts to get the daughters to Ohio. “My daughters decided to go to the UN to help them, but nobody helped them and no one even listened to them.”

“As for me here in the USA, it will be almost 3 years without me seeing my daughters. I am on the verge of having a nervous breakdown. From a long time ago I knew that the UN’s main purpose is to bring separated families together. Please help me bring my daughters to be here in the USA with me.”

Amjad

Over five years ago, Amjad ran a grocery store in a town near Damascus, Syria. He has a wife and three children the ages of 4, 6, and 7 years. When I asked Amjad why his family finally left Syria, he said,

“We grew tired of our children seeing the bodies of the dead.”

- Amjad’s three children

“My family and I got bombed. My shop and home were bombed and robbed. The bombing continued for about 5-6 days in August 2012 and over 850 young people died. We eventually moved to Jordan where I had a heart attack. My heart stopped for ten minutes.”

“In 2014, the United Nations asked if we wanted to go to the United States. When we first got to Toledo, we wound up waiting in the airport for 1.5 hours. I was feeling sick from my heart condition and none of us knew English. It was difficult communicating with the airport personnel and trying to find the resettlement worker assigned to our family. We didn’t even know how to say, ‘I need help.’”

“I only had $50 when we arrived in Toledo. We even had to sell our furniture in Jordan to get a cab to the airport. Our new apartment was cold and my family and I slept on the floor on blankets. I wondered to myself why we came to this country only to have no food or beds.”

“Later that evening, a neighbor knocked on or door and asked me if we needed anything. The neighbors bought us food. By midnight, our beds arrived. The next day, the resettlement worker took me to buy groceries with the $50 I had to my name. Afterwards, I had to go sign the apartment lease.”

“We didn’t get a phone until 23 days after we arrived. We couldn’t communicate with our family to say that we made it to America safely. We had a few toys for the kids, some beds, a table and a couple of chairs.”

(Author’s note: Amjad did not want to be directly photographed for this project out of fear for the safety of his family in Syria; he asked that his children be photographed instead.)

The American Dream

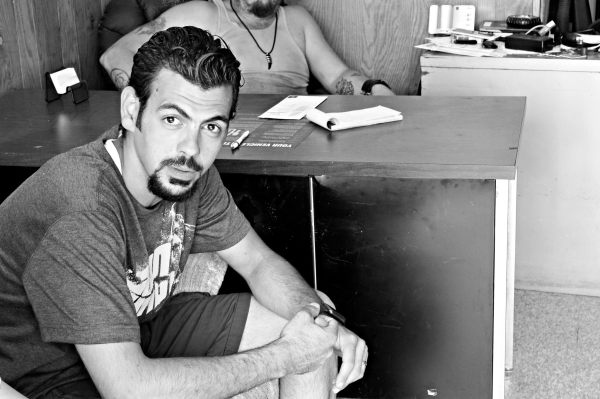

- Shane and Nashwaan

At the end of my visit with Nashwaan, he and Shane dropped me off at a local coffee shop. They let me take their portraits, teasing each other with kisses on the cheek and kindly jabs. Our visit was a happy and welcoming one, with many smiles, laughter, and hospitality.

The jokey camaraderie between the two men was a jarring but welcome conclusion to our daylong conversation of kidnappings, war, and making ends meet. We also talked a lot about the “American dream.” Was the dream just a myth for these refugees who were still in limbo or in the early days of their resettlement? Would they ever get to where my family was – a now well-established first generation family from Pakistan that called Ohio home since 1980?

If there is room for them in the American dream, it will mean that they have a chance to eventually make ends meet, find a safe place safe where children go to school without fear of kidnapping, and live without bloodshed between tribe, religion, political party, and neighbor.

Taking in those who flee conflict, persecution, and discrimination is an action that lies at the bedrock of American democracy. When they weren’t from Syria and Iraq, the refugees came from famine-plagued Ireland, post-war Germany, from ravaged parts of Africa, and the Balkans.

But is there room for them in Trump’s America?

Shane still hopes so:

“We try to foster in our clients a chance to give back. There is a new American dream. Getting your own business and house – that old dream is not possible. But the new one can be about helping others. No matter what religious background. There are a lot of scars that people have when they come here and just crossing the salt water doesn’t heal what happened; people here are still hurt and scared. What they exemplify is not just doing well here, but also loving people who come from a background that hurt them – they learn to love them – and that is what we are trying to produce more of. We see it among Christians, Shias, Sunnis, but they are coming together to help each other and respect each other.”