Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif will meet President Barack Obama at the White House on October 22.

The press release about the visit says it will “highlight the enduring nature of the U.S.-Pakistan relationship” and “strengthen our cooperation on issues of mutual concern, including economic growth, trade and investment, clean energy, global health, climate change, nuclear security, counterterrorism, and regional stability.”

But what are they really going to talk about?

In my latest article in Foreign Policy, I write that Obama will push Pakistan to play a positive role in Afghanistan while Sharif will lobby for continued financial support for Pakistan.

Sharif’s team in Islamabad has said the visit will focus on improving bilateral relations and include a discussion of nuclear security.

The visit got me thinking about how this time compares to other visits of Pakistani heads of state to Washington, D.C.

Since 1950, there have been 40 visits in total by Pakistani presidents, prime ministers, and one governor general. A quick review of the briefing books, memoranda of conversations in the oval office, and itineraries for some of these visits shows one thing:

Pakistan maintains an enduring strategic importance to U.S. national security interests, despite the fact that the relationship often requires unpopular, unfeasible, or illogical tradeoffs for both American and Pakistani leaders.

Below is a sampling of those Oval Office conversations through the decades:

1961 – Ayub Khan and John F. Kennedy

When Pakistani President Ayub Khan met President John F. Kennedy in 1961 during a state visit, the United States needed Pakistan’s help to fight the global communist threat. Knowing this, Ayub came prepared to ask for money.

A military general who became president in a bloodless coup in 1958, Khan was responsible for what many consider a “moth-eaten Pakistan,” a newly independent nation stripped of its best parts (which had gone to India).

Khan, justifiably, asked Kennedy for $945 million for a Five-Year development plan; over one-half billion dollars in foreign exchange for water-logging and salinity control; and $1.4 billion in P.L.-480 food aid.

Kennedy’s advisors identified these requests as problematic because “the GOP has presented requests for more than we are prepared to offer.”

As a result, Khan didn’t get all of the aid he asked for, but the United States still allocated nearly one-half billion dollars for military assistance that year.

The U.S. policy stated that such support was meant to “produce in Pakistan a climate favorable to the maintainence of certain existing U.S. military facilities important to our national security, and to the willingness of the Pakistan government to grant such additional facilities as may be needed.”

GIving Pakistan so much money didn’t make complete economic sense to the United States, but that didn’t matter as long as Pakistan supported the U.S. cold war against the Soviets.

Read more in Kennedy’s declassified “Pakistan: Security Briefing Book” prepared in advance of the Khan visit.

1975 – Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Gerald Ford

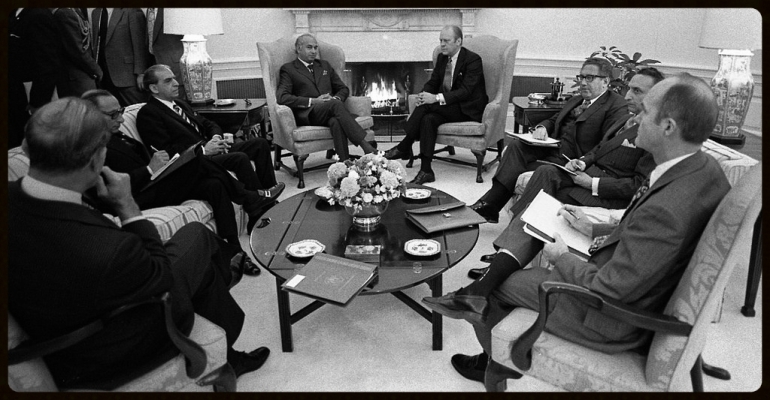

On the morning of February 5, 1975, Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto met President Gerald Ford and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger in the Oval Office.

The men discussed the need to lift a U.S. arms embargo on Pakistan and jumpstart weapons sales to Pakistan in light of India’s testing of a nuclear device in 1974.

Kissinger stated that if “we could say to the Congress that we had discussed your nuclear program, that would help much. If we could say we achieved some nuclear restraint for some help in conventional arms, that would really defuse the opposition.”

Bhutto’s reply: “We will have a nuclear program, but if our security is assured, we will be reasonable.”

Just twenty days later, President Ford lifted the arms embargo, allowing sales of military equipment to both India and Pakistan on a cash basis only.

Read more in the declassified White House Memorandum of Conversation.

1982 – Zia-ul Haq and Ronald Reagan

The U.S. Cold War strategy seemed to eventually pay off, as the United States relied on Pakistani intelligence to funnel American weapons and cash to anti-Soviet mujahideen in Afghanistan during the 1980s.

But news of Pakistan’s expanding nuclear program challenged the longstanding nonproliferation policy of the United States, throwing a wrench into Washington’s strategy of relying on Pakistan to protect its national security interests.

In advance of President Zia-ul Haq’s December 7, 1982 visit to the White House, Secretary of State George P. Shultz wrote in a November 26 memo to President Ronald Reagan:

“Our efforts to block Pakistan’s nuclear weapons programs have taken two tracks. First, we have begun to build a new security relationship, including a significant aid package. We have hoped that this would reduce the principal underlying incentive for acquisition of nuclear weapons. As the elements of that relationship have been put in place, we have been trying to persuade Pakistan that acquiring nuclear weapons is neither necessary to its security nor in its broader interest. However, Pakistan’s nuclear program is motivated in large part by fear of India, and we are unwilling to provide a security guarantee against India.”

In the end, the United States decided it didn’t want to jeopardize the benefits of working with Zia, who ended up receiving billions of dollars of U.S. covert and overt aid during his eleven year tenure.

Read more in the Shultz memorandum to Reagan on “How Do We Make Use of the ZIa Visit To Protect Our Strategic Interests In the Face of Pakistan’s Nuclear Activities”

We can work it out. Sort of.

Obama and Sharif meet during a new era for the U.S.-Pakistan relationship. After the United States killed Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan, some believed it was the end of the relationship. But American dependence on Pakistani air and land routes to supply the war in Afghanistan was too great and the relationship endured.

Pakistan playing a positive role in Afghanistan and putting limits on Pakistan’s nuclear program – among the issues up for discussion this week – don’t seem like easy fixes. But if history teaches us anything, the United States and Pakistan seem to eventually work it out, sort of.

Listen to: “We Can Work It Out” by The Beatles